Violence as a Public Health Problem: A Most Violent Year

Lloyd I. Sederer, M.D.

Take a look at this interview between famed film director J.C. Chandor and violence control expert Dr. Gary Slutkin showing their remarkable resonance and shared mission:

JC Chandor, the writer and director of A Most Violent Year (Participant Media, 2014) saw how the school shooting in Newtown, CT, the town next to where he is raising his family, led to arming security guards. He understood that guns would spawn more violence, not less. He was moved to cinematically paint the story of violence, using a lawless New York City in 1981 as his canvas. He didn't realize at the time what all that had to do with public health.

Gary Slutkin, M.D., left a comfortable life as a physician practicing in San Francisco to spend 10 years in Somalia, Uganda, Rwanda and other African countries fighting TB, cholera, and HIV/AIDS. He was an infectious disease doctor. He knew how to detect a communicable disease, interrupt its transmission, prevent its future spread, and work to change the culture and behaviors of a community to confer immunity against its deadly return. Having done his share of God's work, he returned to the States, imagining a different professional life.

But Dr. Slutkin was far too expert a public health doctor to not apply his medical knowledge to the violence that infests our cities. He saw teenagers killing other teenagers. He saw how the patterns of violence transmission replicated those of infectious diseases, and the utterly ineffective approaches employed to stopping its deadly contagion, especially punishment or trying to "fix everything." His work as a public health doctor would resume, only with a different pathogen -- namely thoughts and expectations of others instead of bacteria and viruses.

Chandor and Slutkin were, however, distant actors on the violence prevention stage until Participant Media made for their introduction. Participant Media (Company With A Conscience has as its ethos joining cinema (and other forms of digital media) with social mission: their more than 60 films include The Help, Good Night, and Good Luck, Syriana, An Inconvenient Truth, Food, Inc., The Soloist, Waiting for 'Superman', Lincoln and Contagion (ever timely with Ebola this year).

As a result, two creative endeavors now find themselves joined: A social action campaign, from Participant, and Cure Violence, the non-profit organization founded by Dr. Slutkin that has had extraordinary success in controlling urban violence in cities throughout the world using public health, disease control methods.

Dr. Slutkin, in New York City for the premiere of A Most Violent Year, remarks that ending urban violence requires: identifying the sources (people and locations) of its transmission; using community workers (locals, natives if you will, who know their neighbors and their culture) to interrupt the transmission of violence; and changing the culture, the norms of a community -- replacing "prisons with parks." Cure Violence, is now working in 25 cities (over 50 communities), including Chicago, Baltimore, seven New York cities (including NYC, Albany, Syracuse, Buffalo), as well as in Puerto Rico, Mexico, Honduras, Jamaica, and South Africa. Reductions in violence of over 30 percent in year one of a program, and up to 70 percent in time, have been replicated 20 times and independently validated again and again. Dr. Slutkin likes to say the health approach to violence is "not a metaphor" -- that the treatment works, proving ipso facto, that indeed violence is a contagious process.

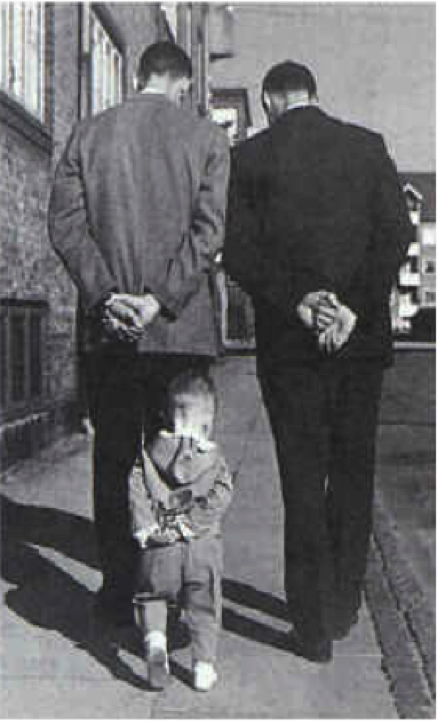

Cure Violence appreciates that kids killing kids is the product of biological and group processes. This type of violence is a learned behavior: proximity and ongoing exposure to violence in a community triggers youth to imitate what they see. Our brains have "mirror neurons" that automatically incorporate and replicate what others of influence in our lives do.

Approval by peers (including gangs) is a force that then powerfully rewards the behaviors around us, in this case violence, likely using surges of brain dopamine. Alternately, disavowal by peers, isolation, is mediated by the same brain circuits as physical pain, a feeling we want to avoid at all costs. Adding to this complex mix of chemistry and cognition is trauma: most youth at risk for violence have been physically or mentally abused. Trauma destabilizes the limbic, or emotional, system in the brain inducing heightened sensitivity to slights (disrespect) and the unmodulated, rapid escalation of aggressive responses. Trauma also impairs the executive brain (the prefrontal cortex) from being able to put the brakes on an impulse, which is needed to slow down a feeling becoming an action.

Chad Boettcher, Participant's executive vice president for social action and advocacy, has the great job of linking a film with a campaign that "...inspires and compels social change." He approaches his work like a social scientist: he studies a film's relevance to policy makers and its capacity for impact as measured by a set of metrics that assess its emotional impact and ability to move people to act. In the case of the campaign for Cure Violence, he also saw a theory of change, a concept of what the problem is and who could and how to make it better.

The social action campaign that today bonds A Most Violent Year with Cure Violence means to change our minds about urban violence, to redefine it as a disease with effective interventions, not as the crimes we continue to punish fruitlessly. Dr. Slutkin wants the campaign to better engage the public health sector in curing violence: to increase the number of health workers ("violence interrupters") and health departments using this method; he wants to see our news and social media language use the science of health rather than the moral lexicon of punishment.

Jonathan King, executive vice president for narrative film at Participant, believes that "... a good story well told can make a real difference..." His job is to find films with social meaning that can be delivered with artistry and quality yet are commercially viable. Looking at Participant's film credits in his eight years there, he seems to be doing just fine. He had been tracking JC Chandor's work (recently, All Is Lost and Margin Call). After Chandor showed King the script he had written in the wake of Newtown they were soon in business together, including recruiting Jessica Chastain, Oscar Isaac, and David Oyelowo to star in the production. In 18 months, blazing fast for a movie, they wrapped up the film.

Changing how a society thinks and behaves is a daunting process. It takes missionaries and heroes. Recall what Gandhi said: "First they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, and then you win." The tradition of non-violence, the spirit of changing the world through story and collective enterprise, is honored by the work of Chandor, Slutkin and a media company with a conscience.

My film review of A Most Violent Year will appear in The Huffington Post on 12.31.2014.

=========

Dr. Sederer is a psychiatrist and public health physician. The views expressed here are entirely his own. He takes no support from any pharmaceutical or device company.